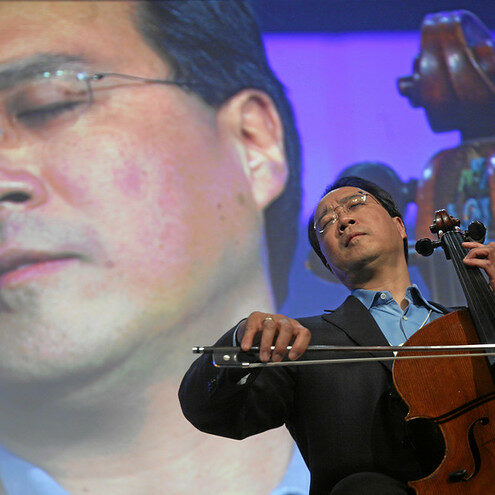

Here’s my heretical statement of the week – I’m not a huge fan of Yo-Yo Ma’s legendary 1983 recording of Bach’s cello suites.

Yo-Yo Ma needs no introduction. He’s the most famous and celebrated cellist and one of the premier classical musicians of the past forty years. He’s recorded Bach’s cello suites, the most widely recognized pieces of cello music, multiple times, with the 1983 recordings achieving worldwide recognition and praise and winning a Grammy for Best Instrumentalist Solo Performance. They are indeed virtuosic, displaying a mastery of technique. But they also have an almost airless delivery – Ma is playing the notes, but the emotion behind them isn’t fully present. They lack the intensity of their first recording by Pablo Casals or the weight of French master Pierre Fournier. Casals plays with abandon, Fournier plays with passion, and Ma plays with precision.

As a child, Casals famously discovered Bach’s suites in a thrift shop and would go on to introduce these pieces to a worldwide audience. They have since become a staple of cello repertoires and have been transcribed for almost every other classical instrument. The prelude to the first suite is one of the most recognizable pieces of classical music – you’ve heard it even if you don’t know you’ve heard it. The six suites all follow the same structure: a prelude followed by five movements meant to accompany different styles of baroque dances. While the notes on paper exist, no original manuscript in Bach’s hand has ever been discovered, and the copies of the suites that have been circulated lack specific performance notes, leaving players room to interpret the music and reflect their own personality and intent.

Young Yo-Yo Ma was intent on playing the bejeezus out of the notes, rushing through passages at a speed that might have strained an 18th-century calf or two had dancers accompanied his playing. His first recordings show off his prodigious talent but lack the perspective of an experienced master. Ma joked in a 2018 New York Times feature that it had a “youthful ‘I know everything’” air.

Casals and Fournier both recorded their performances of the cello suites when they were in their 50s, and Ma recorded them for a second time in 1997 (Inspired By Bach) when he was in his early 40s. His playing here is more human but still tighter than the works of other masters. His most recent, and likely last, recordings were released in 2018 (Six Evolutions: Bach Cello Suites) in his early 60s, after a lifetime of playing, exploration, and plaudits at the highest level.

Here, he comes closest to perfection. His skill hasn’t diminished, nor has his feel for his instrument. His love of the music is palpable, and his playing finally conjures the imagery of the emotions in the music – joy, sorrow, melancholy, and reflection. It sounds like a lifetime of passion and experience rather than sheer talent. They say that wine gets better with age, and so, too, do musicians.

Photo: Andy Mettler, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0