Our culture has a plethora of wise sayings about how to use words – “brevity is the soul of wit,” “less is more,” and “show, don’t tell,” for example. It’s easier said than done. As storytellers, we have an impulse to expand, shade, contextualize, and describe. It’s certainly a treat to enjoy something voluminous, but it’s equally satisfying to enjoy something taut and focused. Plenty of songwriters can produce a novel. The Dylans, Cohens, Mitchells, Springsteens, and Joels of the world are rightly lauded for their ability to conjure stunning imagery and emotion with their descriptive lyrics. But it’s equally moving and somewhat rarer for a lyricist to do the same thing within a much tighter word budget. Neither style is superior; the literary world has room for both Charles Dickens and J.M. Coetzee, as the art world has for both Courbet and Matisse. A great songwriter is a great songwriter, whether they use two verses or twelve, and a great song is a great song, whether it’s three minutes or thirteen.

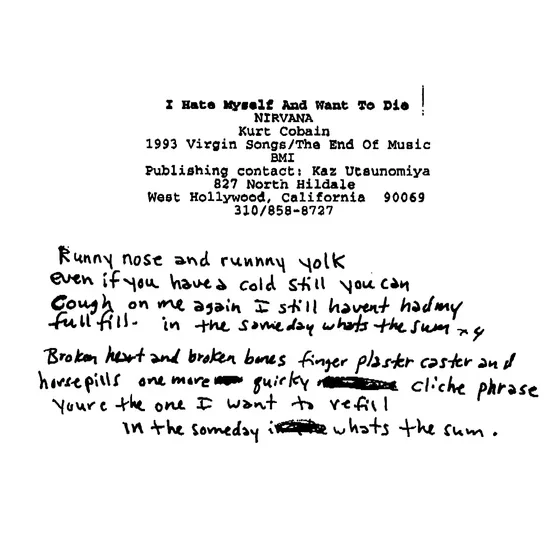

One of my favorite examples of lyrical economy is the Nirvana song “Sliver.” Kurt Cobain relates a complex narrative in twelve impressionistic statements and one repeated phrase as a refrain. His brief lyrics evoke sadness, pain, and a distinct sense of place and memory.

Another master of this is Lucinda Williams, who uses impressionistic phrases to create vivid scenarios in the minds of her listeners. “Car Wheels On A Gravel Road” dredges up a lifetime of movement, unrest, hope, fear, and ennui through simple couplets:

Child in the backseat about four or five years

Lookin’ out the window

Little bit of dirt mixed with tears

Car wheels on a gravel road

She lets us create our own imagery in the empty spaces around her lyrics. Where is the child going? Why are they crying? What are they hoping to see out the window? It’s a powerful image that is both specific and timeless. She does this all the time. On “Greenville,” a song presumably directed at an ex, all she has to say is “Empty bottles and broken glass/Busted down doors and borrowed cash” (among other things, the whole song is devastating), and we know precisely what sort of person she’s describing. Again, we can fill in the blanks and what we imagine is more personal and powerful than anything else she could tell us about this jerk.

Then there’s Paul Westerberg, whose phrasing can be so exact that I wonder what happened to him that inspired such gems as “How do you say I’m OK to an answering machine” (“Answering Machine”), “Jesus rides beside me/He never buys any smokes” (“Can’t Hardly Wait”), “Ain’t lost yet so I gotta be a winner/Fingernails and cigarettes, a lousy dinner” (“I Will Dare”), the list goes on and on. He’s able to state such specific ideas that it’s almost impossible to imagine him saying it any other way. And that’s why he’s brilliant. Like Cobain and Williams, he uses simple phrases to express a precise idea and a hint at a much larger story.

There’s a powerful beauty in the way Bruce Springsteen can wax poetic about a street race or how Billy Joel can describe the pathos of a couple whose lives have changed, and there will always be a place for writers who can describe fine detail as they do. But there’s an equal beauty presented by those who let us provide our own details.