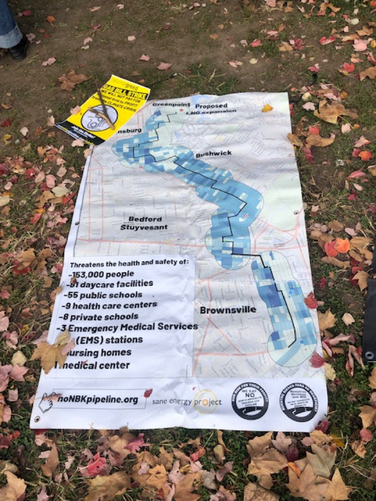

For the past two years, a coalition of Brooklyn-based climate activists has been demonstrating in opposition to a fracked gas transmission pipeline project (Metropolitan Natural Gas Reliability Project) running from Brownsville to Greenpoint. While Phases 1 through 4 of the pipeline are already completed, National Grid is still seeking permission from the New York Public Service Commission (NYPSC) to continue extension of the pipeline north of Montrose Avenue in Bushwick; expansion of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) storage at a depot along Newtown Creek; and permission for LNG trucks across city limits. The coalition’s efforts have been mounting since its first strike in September 2019, and have grown louder and more robust since the NYPSC’s approval of National Grid’s August rate review filing referencing Phases 1 through 4 and the company’s failure to publish its Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA) assessment of the Vaporization Project before its October 21, 2021, information session.

Most recently, Sane Energy; partnering environmental groups; neighbors; and legislators like Senator Julia Salazar, Comptroller Scott Stinger, and Assembly Member Joseph R. Lentol expressed dissent for the rate hikes and the Vaporization Project – one of the many legs of the Metropolitan Natural Gas Reliability Project, known in the neighborhood as the North Brooklyn Pipeline Project, that plans to replace two old vaporizers and add two new ones to the Greenpoint facility. On November 22, 2021, Sane Energy and affiliates released a rebuttal to National Grid’s CLCPA analysis, which was finally released on November 1, 2021, accusing the company of falsely claiming that upstream and downstream greenhouse gas emissions will be stagnant with the implementation of new vaporizers; grossly underestimating emissions from the Vaporization Project; failing to run analysis on the potential impacts on disadvantaged communities; spending dramatically less on energy efficiency and demand response than on infrastructure that increases reliance on fossil fuels; and more.

The pipeline project has quickly become convoluted and opaque to residents in the neighborhoods of the build-out because National Grid has segmented the job into various smaller ones. These include disparate installments of the 6,200-foot pipeline across five Phases, vaporization replacement and addition, and trucking transport of LNG gas to and from North Brooklyn. Kim Fraczek, Sane Energy’s Director, explains the segmentation as a means of weaseling out of emissions laws because the smaller jobs alone do not surpass approved levels of greenhouse gas output. “Where I grew up in Pennsylvania, my family’s water is now poisoned because of fracking infrastructure. They’re not looking at the emissions in the land and water just a little west and south of here, they can’t say they’re following a climate law if they’re not looking at cumulative impacts.” It is illegal to frack in New York, so National Grid outsources the job to drilling companies in Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

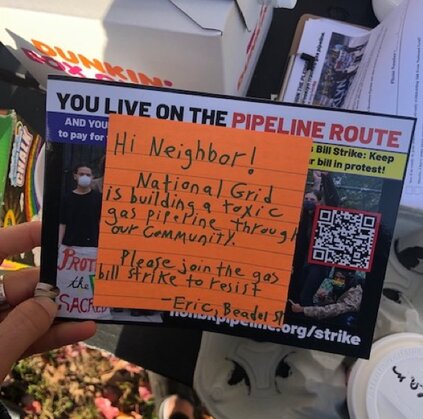

Fraczek says this segmentation also makes it extremely difficult to organize against the entire project, and that is a big reason community activism and outreach is so important. Along with resisting rate hikes and the Vaporization Project, the coalition also organizes protestors in solidarity with their neighbors for events like writing postcards to personally invite those most directly impacted to rally for their power back. On November 21, a group of eleven individuals, with a few others floating in and out, from the community and other environmental activist groups like Bushwick Eco Initiatives gathered around two picnic benches in Cooper Park to write to their neighbors, “We live on top of a dangerous fracked gas pipeline! I joined the gas bill strike in protest. I hope you will too.” Amanda Lyn says she’s come across a lot of people during flier-ing and community outreach still unaware of the project. “I think if people knew this was happening, they would be really angry about it. Nobody wants this in their community.”

“Public power as the goal is like the guiding light or the north star. This is saying, ‘we have something that we are asking for – to take the decisions of how our neighbors keep their homes warm out of the hands of a private company and put that in the hands of those people and our elected officials – where there is a much greater measure of accountability and level of oversight and level of prioritization.” Kevin LaCherra, a fourth generation Greenpointer, elucidates the environmental and social devastation continued investment in his grandparents’ oil and gas industry would cause his community. “It’s a survival incentive for the rest of us, it’s a profit incentive for them,” he says.

Eric Kun sits before the thickest stack of personal notes he’s signed and stuck on postcards to deliver to neighbors that afternoon. He joined the first class action lawsuit on behalf of Sane Energy against National Grid and has been protesting with the coalition for the past two years with a vigor for educating and organizing his community. He says, “we already have too much truck traffic. Trucks are allowed to get variances so they can get a 55-foot trailer or even longer coming through the neighborhood. And where I live – just walk the street, it’s a game of Frogger.” In National Grid’s proposal is the request for a variance from the city to bring LNG trucks into the city, something Fraczek flags as illegal. The trucks will transport fracked gas from outside the city, through Queens and The Bronx, to processing facilities at the mouth of the pipeline in Brownsville.

Kun then acknowledges that increased fracking, trucking, and pollution from the entire pipeline project will only exacerbate the substantial rates of asthma in North Brooklyn. Fraczek explains the shale formation under Pennsylvania and West Virginia that National Grid’s partner drilling companies are fracking “is highly radioactive. So there’s radon being carried into our homes when we turn our stoves on. It’s the leading cause of lung cancer in non-smokers in our country. It’s very aggressive for people who have asthma.”

Sitting next to Kun with nearly as thick a stack of her own appeals to neighbors, Lyn speaks to the need for an investment in green homes. “We have the technology available to be able to transition away from [gas]. If we transition those [fossil fuel] funds to making buildings fully electric, being able to have solar panels, have wind energy, have heat pumps, then that’s very possible.”

J shares their commitment to demonstrating against the Metropolitan Natural Gas Reliability Project, acknowledging this as a local mode of involvement that could capture their energy better than guilt about not being able to get time off work to demonstrate solidarity with those resisting the Dakota Access Pipeline or Line 3. John, a Bushwick resident who also runs Bushwick Eco Initiatives works in the environmental sector but says his paid job does not have the same potential for impact as does social organizing that educates people about local approaches to climate resilience. It has been pressure from this organized community of climate and social justice sympathizers, postcard-writers, and neighborhood organizers that suspended National Grid’s rapid build-out in the midst of the pandemic against the state’s “shelter-in-place” recommendations; compelled elected officials from city council up to federal office to join in opposition; and has built a robust coalition of residents from Brownsville to Greenpoint. Further community action Sane Energy urges is withholding $66 of utility payments in reference to the estimates of what consumers would be expected to pay over three years for Phases 1 through 4; signing a petition against the vaporization leg of the project to be decided on December 6; and organizing at further protests.

After about two and a half hours, people lift themselves from Dunkin’ coffee cases and near-empty Munchkins boxes to huddle around Anna Leidecker and Lee Ziesche for instruction on distributing postcards – a group of community members representing neighborhoods without much historically to do with each other and showing up for unique reasons. “It’s about present community,” says Kun. “And it’s about our collective future.”